MOGADISHU, Somalia 2 May 2023 – On World Press Freedom Day, the Somali Journalists Syndicate (SJS) is concerned about the increasing use of Facebook Community Standards and mass reporting to suppress and censor Somali journalists whose reporting is deemed critical to the Somali government which resulted to content take down, restrictions of freedom of expression and deletion of social media accounts.

Ahead of WPFD2023, SJS interviewed nine online journalists and five local media stations who all described how their news content was censored, restricted, removed or made less visible through mass reporting by anonymous Facebook users. Some of the journalists and media stations we interviewed have reported that their pages were banned from posting, made to respond to fake copyright claims or their pages deleted for good as attackers exploit Facebook’s Community Standards in a devious tactic to suppress independent journalism.

Among the content targeted is articles, video interviews, news pieces and pictures critical to the Somali Federal Government, the Ministry of Information, the National Intelligence and Security Agency (NISA) and the police. Journalists have also reported that mass reporting has led to the removal of news report that alleged the police commanders of wrongdoings including sexual violence against women and other abuses.

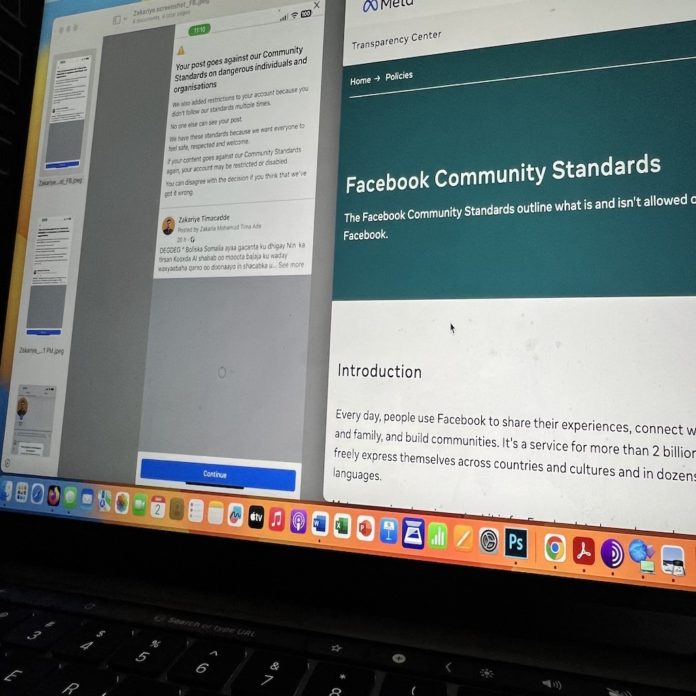

The diaspora-based Somali journalist Mohamud Mohamed Dahir (Mohamud Arab) was forced to remove his video interview on 10 April 2023 which became viral and exposed human rights violations in the Mogadishu detention centres run by NISA. According to Mohamud Arab and a review of Facebook After the journalist appealed against the decision, the interview was re-posted but with restrictions describing it as “dangerous content or dangerous individual.” The restriction has since been revoked due to a second appeal by the journalist.

“They [attackers] mass report almost every report I post on my Facebook page. This has led Facebook to take down some of my content and my account was flagged. When I appeal, Facebook does not respond quickly and it has made me to worry about what I can publish online,” Mohamud told SJS.

Mohamud and three other journalists were detained by the national intelligence in August 2014 for their critical reporting on authorities. They were freed on early 2015 and has decided to flee the country into exile.

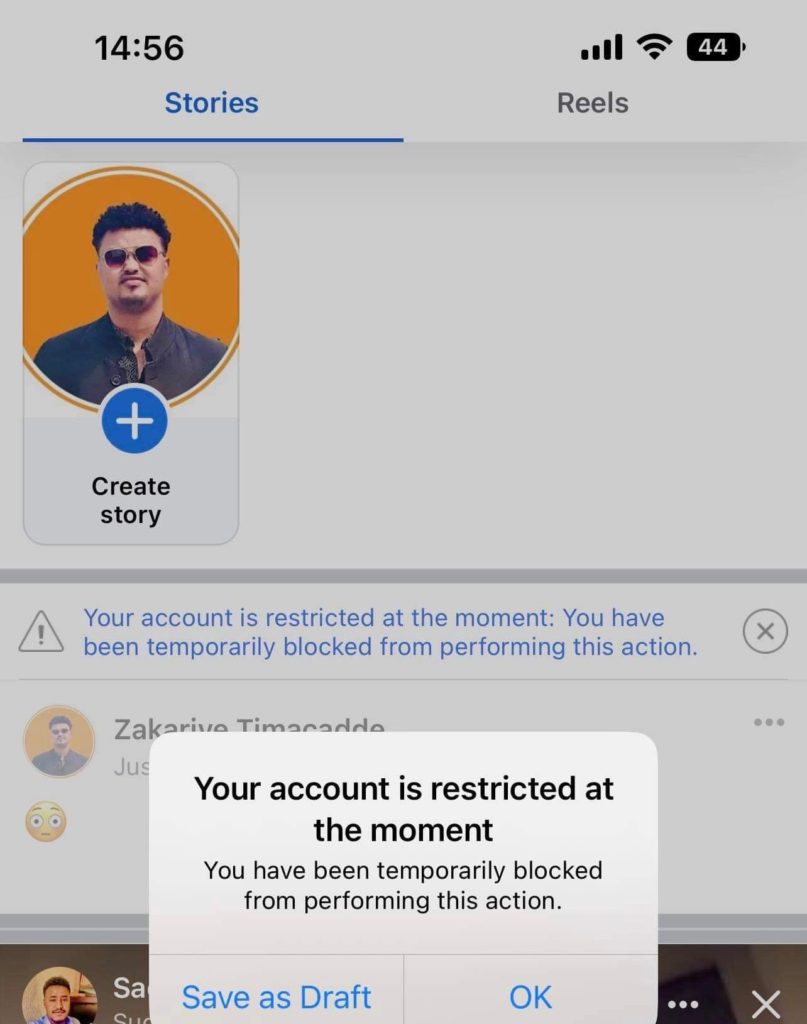

Similarly, diaspora-based journalist Zakariye Timacadde has been repeatedly under attack since end of 2022 following his reporting on allegations of corruption, insecurity, sexual violence and power abuse by the Somali police and other powerful individuals at the National Intelligence and Security Agency (NISA). In mid April 2023, he received a message from Facebook notifying him that his “account is restricted at the moment”.

“When I fled the country due to my security, I decided to continue reporting what is happening in the country remotely. But now, like many other journalists, they started to attack me online,” Zakariye Timacadde told SJS.

Zakariye fled into exile in June 2019 after he faced threats for his reports on sensitive security issues by the national intelligence and al-Shabaab.

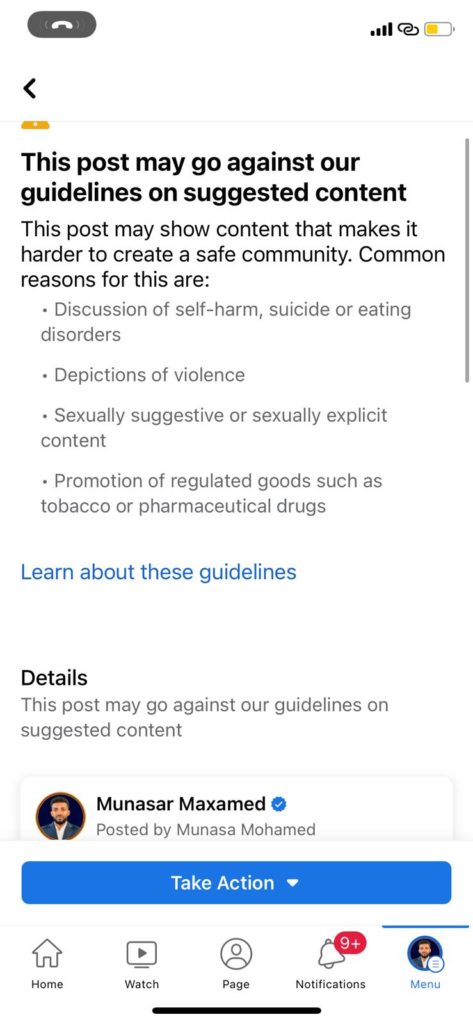

Another diaspora-based journalist Munasar Mohamed. On 27 April, he covered a leaked video exposing officials selling stolen food aid at a local market. His Facebook was then put on restriction to which he appealed to Facebook. Days earlier, he published a commentary video and on the same day Facebook removed the video as he received a notification from Facebook which states “this post may go against our guidelines on suggested content”.

“It is endless. Every single day, I receive messages from Facebook indicating that my content goes against Facebook’s community standards even if I interview someone or post an article. This is a justification used to silence journalists like me,” Munasar told SJS.

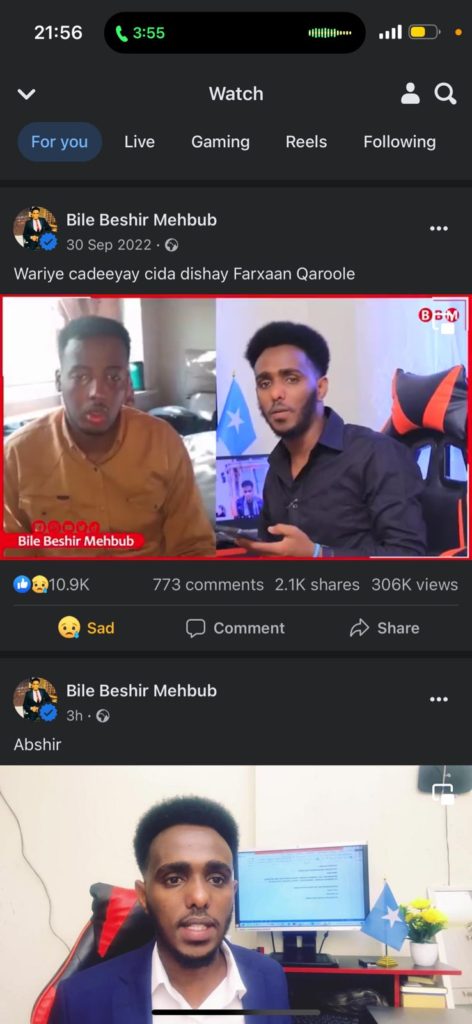

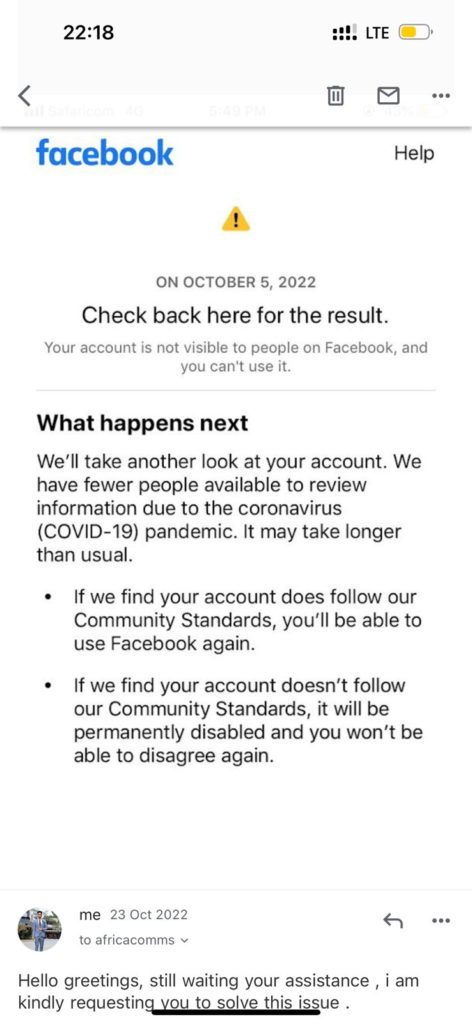

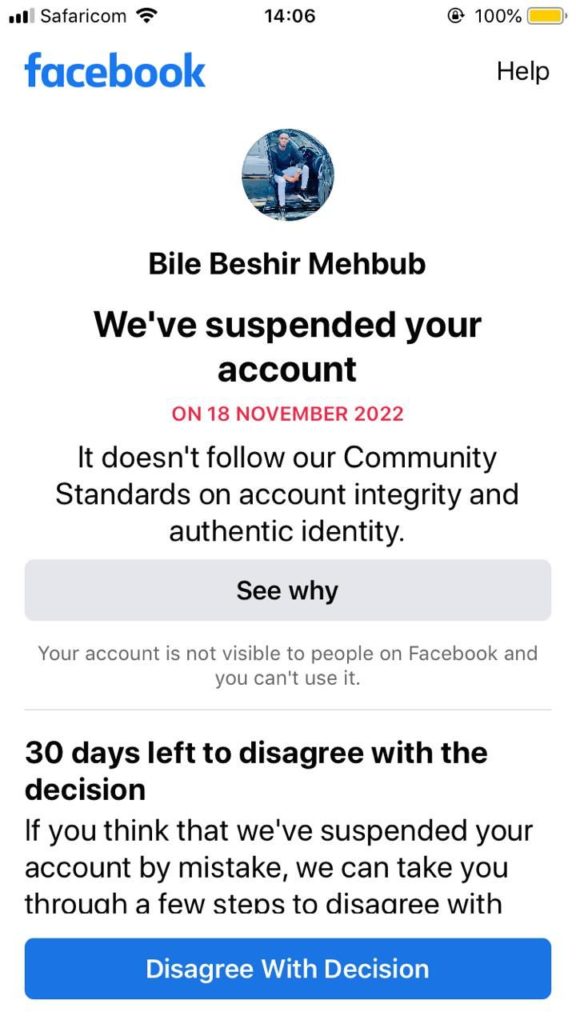

On 5 October 2022, Nairobi-based journalist Bile Bashir Mehbub received a message from Facebook notifying him that his Facebook page “was not visible to people on Facebook” and that he could not use it. That was few days after posting a video interview with another journalist analyzing a bombing attack that killed former Banadir police commissioner, Farhan Qarole during an al-Shabaab attack on 30 September 2022. “I contacted Facebook but I have not received any explanation,” he told SJS. A month later Bile had created a new account under his name only to be suspended on 18 November 2022. A message from Facebook then said “We’ve suspended your account. It does not follow our Community Standards on account integrity and authentic identity.”

SJS Secretary of Information and Human Rights, Mohamed Ibrahim Bulbul, who also reports online was not spared. “I stopped covering issues related to al-Shabaab because of the fear that I will be targeted physically and online. Since October 2022, local journalists who report al-Shabaab related incidents are their online platforms such as their Facebook pages taken down or even hacked,” Bulbul said.

That is not the end, posting articles and videos that expose abuses committed by NISA including attacks against journalists can bear a high risk for journalists themselves and their online platforms. “Anything to do with insecurity, or attacks against journalists or even to call for accountability for crimes against journalists or other human rights violations will put your online platforms at risk,” he said.

Three other journalists Abdirahman Nuur Abukar, Mohamed Bashir and Khalid Foodhaadhi, and representatives from Risaala TV, and its sister radio Radio Risaala as well as Kaab Somali TV have told SJS that their content were similarly targeted leading to avoid criticism of the authorities.

On 23 April 2023, Somaliland news site reported that a court order issued by the Marodi-Jeh District Court instructed local telecom companies to block access to the social media accounts such as Facebook, Youtube and Twitter belonging to several individuals including journalists and other critics. All of them have been publishing news and commentary articles about the Laascaanood conflict. The court order was issued in January 2023 but has not been implemented yet.

“The use of mass reporting has caused journalists to worry about the type of content they can report because they feel it is not safe for them. We strongly condemn these type of suppression and censorship of journalists as the Somali authorities continuously abuse the reporting system of Facebook by giving false information because they know that Facebook’s computerized moderation and its algorithms will have difficulty in comprehending the Somali language which the content is reported,” SJS Secretary-General, Abdalle Ahmed Mumin said “This form of censorship is now having a huge impact on journalists and local media houses because it not only induces fear, it silences journalists and discredit them professionally.”

For majority of the content put on restrictions or removed, SJS has found that Facebook constantly categorized it as ‘Dangerous organisations and individuals’ which is part of Facebook’s six section Community Standards policy. A review done by Article19 in 2018 found that these Community Standards are not in line with international human rights law while Facebook has failed to to provide more information about the way in which those standards are applied in practice.

“Facebook and other social media companies should be more transparent and explain how they comply with various governments including the Somali authorities when it comes to censoring or banning content produced by journalists,” Mr. Mumin said. “We also urge Facebook to review its broad definitions of ‘terrorism’, ‘hate speech and incitement to violence’, or ‘content that is not allowed’. Facebook and other platforms should align their definition of ‘terrorism’ with that recommended by the UN Special Rapporteur on counter-terrorism. In particular, Facebook should avoid the use of vague terms such as ‘praise,’ ‘express support,’ ‘glorification’ or ‘promotion’.”